Kategori: startsida

A Heart From Jenin

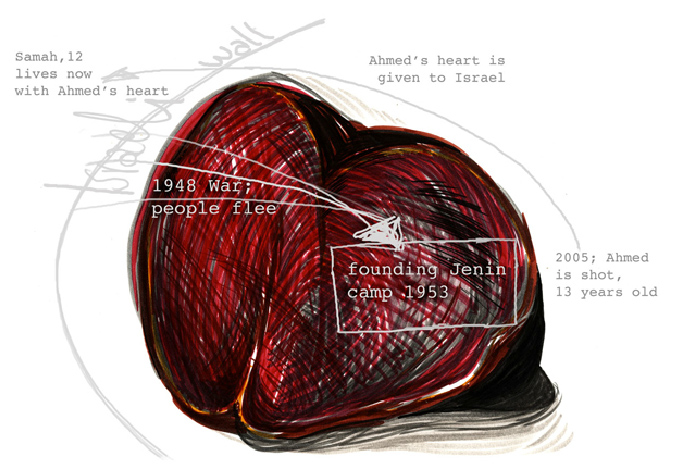

A Heart From Jenin, 2006

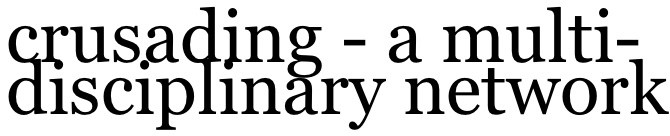

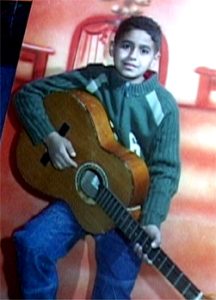

The film is about Ahmed, a Palestinian boy who lived in the Jenin refugee camp, on the West Bank. In November 2005 he was shot to death by an Israeli sniper. He was 12 years old. His parents decided to donate his heart to the other side of the wall, to Israel. Samah is the name of the Israeli girl who now lives with Ahmed’s heart. For Ahmed’s parents their son lives on through the girl as a hope for peace with Israel.A gift can effect change when there is someone on the other side willing to accept it. See the film here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D_57fiImxFc

Ahmed’s mother says that the donation was made in the spirit of ‘Salam’ (peace) with Israel “We are sending a message to the whole world that we love peace. We donated six of Ahmed’s organs to the hospital. It’s in the possession of the hospital to donate, regardless of whether the receiver is Jewish, Muslim, Druze or Christian.” A 12-year old girl Samah, received Ahmed’s heart. The film is also about her living in Peq’in, Israel. She sometimes takes charge of the camera and film. She calls Ahmeds father and mother in Jenin. Samah’s father says that Ahmed’s family can regard his daughter as their own and they sometimes meet.

Ahmed’s mother says that the donation was made in the spirit of ‘Salam’ (peace) with Israel “We are sending a message to the whole world that we love peace. We donated six of Ahmed’s organs to the hospital. It’s in the possession of the hospital to donate, regardless of whether the receiver is Jewish, Muslim, Druze or Christian.” A 12-year old girl Samah, received Ahmed’s heart. The film is also about her living in Peq’in, Israel. She sometimes takes charge of the camera and film. She calls Ahmeds father and mother in Jenin. Samah’s father says that Ahmed’s family can regard his daughter as their own and they sometimes meet.

As a filmmaker I was accepted as someone who could contribute my presence. I depicted the admirable empowerment that every person should fe el that they have: the Palestinian family that gives a gift no politician can give and in doing so breaks isolation when they make contact with the Israeli family that accepts their gift. The gift of the heart drills a hole in the wall – when it’s recieved.

el that they have: the Palestinian family that gives a gift no politician can give and in doing so breaks isolation when they make contact with the Israeli family that accepts their gift. The gift of the heart drills a hole in the wall – when it’s recieved.

Jenin is situated in the North of the West Bank. The refugee camp, which is today a part of the city, is inhabited by 13,000 people. The Camp was built by refugees from Haifa after the 1948 war, and is one of the most frequently targeted areas throughout the history of the Israeli occupation. In April 2002 the Jenin Refugee Camp was totally destroyed by the Israeli occupation forces. The United Nations was not let in by the Israelis until a week after. We were only a few photographers who managed to find a way into the city during this week (I climbed a mountain in order to get in) so there is very limited documentary material. I have uploaded all my photos (around 250 photos) and my writer friend Ana Valdés texts here: https://ceciliaparsberg.se/jenin/

Two months later, in june 2002, Israel started the construction of the wall which stretches from North of Jenin and continues to the south encircling the West Bank. The border between the two countries of the families is partly an eight meter high wall, partly a fence, on the Israeli side the area next to the border is a no-mans-land guarded by military and trained dogs. The Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories began in 1967.

The conflict is difficult and the occupation impacts life in Palestine. I returned to Jenin Refugee Camp in November 2005, to see how it had been rebuilt from the demolition in 2002 (see Jenin). Ahmeds grandparents had fled from Haifa in 1948. When I was there in Jenin, Ahmed was shot dead.

To me, these two families act in a way that illuminates how conflicts can be solved, by making contact and connecting.

THE INSTALLATION HAS BEEN SHOWN AT:

2006 BildMuseet Umea www.crusading.se

2006 Fotografins Hus, Stockholm

2007 LänsMuseet Västernorrland and Jacob’s church Stockholm

2007 – 2008 Malmoe Museer, Malmoe

2008 – 2009 World Culture Museum, Gothenburg www.varldskulturmuseet.se

…and more, se CV

SCREENING + SEMINAR: Lens Politica – Film and Media Art Festival 19.-23.11.2008

Helsinki www.lenspolitica.net MKC, Fittja Stockholm, okt 2008

School of Global Studies, Göteborg, sept 2008 Kulturverkstan, Göteborg, sept 2008

Center for peace Research/Border Poetics group at Institute for Culture og Litterature, Tromsoe Norway, Aug 2008.

FN-Sambandet, Verdenteatret, Tromsoe, Norway. www.fn.no/distriktskontor/nord/internasjonalt_seminar Key Note Speaker at the conference: Sensitive Peace Research, Tampere Peace Research Institute, Univerity of Tampere 16-18 April

…and more, se CV

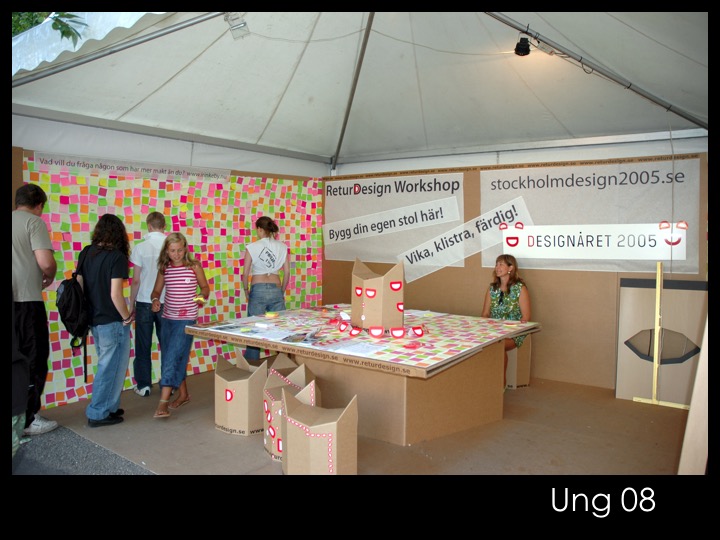

Photos from the exhibitions (click on images to enlarge)

World Culture Museum, Göteborg

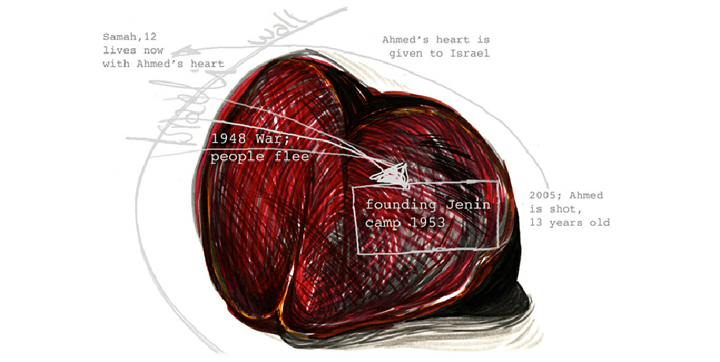

The wallpaper is made of 300 photos of the demolition of the Jenin camp, 2002 (see Jenin) Jenin is – as a shadow – written left to right on one wall and in Arabic; right to left, on the other wall.

Fotografins hus Malmö

The installation consist of: -a shorter version of the film: 30mins -a wall paper: 2 X 6 meter showing 300 photos from Jenin camp, the destruction in April 2002 -a map showing borders, built wall and planned wall -a print of the heart and a drawing of the history: 50 X 70cm

About A heart from Jenin, text by Jan-Erik Lundström, head of Bildmuseet, Umeå (2006)

Cecilia Parsberg’s artistic practice have often brought her towards the hazardous and complex but important and necessary political undertaking in speaking about the other, the marginalized or underprivileged of society (engaging both sexual, social and political displacement and suppression in her work), or the underdogs in a political conflict such as the Palestinians; generating challenging works of art, blending documentation and activism, where often the artist herself is present as witness, investigator, mediator, supporter. Over the last few years, Parsberg has maintained a particular focus on Palestine, the living conditions of Palestinians and life on the occupied West Bank and the Gaza strip, resulting in several projects such as the videos I can see the House or To Rachel, with the story of the killing of the young American activist Rachel, run over by an Israeli tank or the action East or West, Home is Best. One of Parsberg’s visits, in April 2002, coincided with the brutal Israeli army invasion of the village and refugee camp Jenin on the West Bank, during which Jenin was more or less almost completely demolished and many Palestinians killed, the numbers uncertain since Israel blocked any inpendent investigation. Parsberg was able to enter Jenin in the early aftermath of the invasion, managing one of the few documentations of its kind of the extent of the destruction of Jenin. This material became the website www.this.is/jenin, a rich archive of images and written testimonies on the fate of Jenin. The photographs on display in the present exhibition are sourced from this body of photographs, supplanting the website notion of an open source archive with offering the opportunity to re-focus and engage more specifically with individual images and their stories. It does not however change the overall sense of perverse, meaningless, and unbounded mayhem. In the exhibition space, the Jenin photographs are juxtaposed with the video A Heart from Jenin, the artist’s return to a largely rebuilt Jenin in November 2005, three years after the Israeli attack on Jenin. Rebuilt yes, but hardships in Jenin continue.

A Heart from Jenin’s key narrative is the extra ordinary story of Ahmed, a 13-year old Palestinian boy who is shot to death by Israeli soldiers, and becomes clear that the boy will not survive, decides to allow the child’s organs to be donated. The 26 minutes long video traces the actual event of the boy’s casualty through conversations/interviews with the near family, with people from the neighbourhood but also with writers, university professors – one from Israel – and intellectuals, enabling a broader picture of life on the West bank. But it is the gesture of the parents, the donation, which defines the film. For as it turns out, the boy, when pronounced dead, becomes the donor of five organs. His heart is given to a 12-year old Israeli girl from Haifa, who has for years been waiting for a heart transplant and whose life now is saved. The tragic and horrible killing of Ahmed brings out, through the parents’ act of allowing donation, a gesture of reconciliation, of appeasement. Especially that the heart is not a metaphor; the heart of Ahmed lives on in the body of the Israeli girl – as beautifully illustrated in the drawing by Cecilia Parsberg on the journeys and meanings of a heart, presented in the exhibition. Their parents are quoted as saying: “we want them [Ahmed’s parents] to consider our daughter as their daughter”. From those bestowed the most pain come the most human of gestures.

Jacobs church, Stockholm

4U!

Locater East or west, home is best

Private Business

Private Business

First shown at Schaper Sundberg Gallery, Stockholm, Sweden, August October 1999. Public art agency, Sweden bought the two photographs “Corner” and “I Can See You but You Can’t See Me” / “Jag kan se dig men du kan inte se mig” and placed them at the University in Skövde, where they sparked extensive discussion — even involving the Minister of Culture (a long story about art; see below on this page). The photographs are still there.

Another copy of Corner was placed in Umeå at the Department of Gender Studies.

I Can See You but You Can’t See Me / Jag kan se dej men du kan inte se mej was shown in 2011 in the group exhibition Lust och Last at the National Museum in Stockholm, and earlier in the touring exhibition Konstfeminism throughout Sweden (2005–2006), including venues such as Liljevalchs Konsthall. The curator was Niclas Östlind, se bokenKonstfeminism.

Boken och utställningen Konstfeminism fokuserar på olika feministiska strategier i konsten från 1970-talet till idag och lyfter fram konstverk som på olika vis har gett och ger starka avtryck i diskussioner och förhållningssätt till kön, sexualitet, kropp samt mänskliga relationer. Under 1970-talet intog nya tankar och motiv konstscenen på ett banbrytande sätt. Kvinnor utgick från sina egna erfarenheter och lät dessa påverka konsten och debattklimatet — i kontrast till rådande patriarkala värderingar. Det personliga som politiskt område uppmärksammades, samtidigt som det fanns ett starkt engagemang på det globala planet. Även existentiella frågor fick en framskjuten plats.

The large size of the prints is necessary to see all the details. They are analog negatives (Hasselblad panorama camera).

The international egg and spermbank (Analog panorama-negative, C-type print 229X84cm.)

The first photograph, entitled; The International egg and spermbank is of a city and the air space immidiately above it. The air is also an image of an unlimited space, which stems from the fact that many egg and sperm donators and recievers make contact in cyberspace; the collective fertilization space. Cyberspace does not exist as a space, it could however exists as soon as one acts.

(Analog panorama-negative, C-type print ca 229X84cm.)

Title: ”Corner; Athenas emergence” (Pondering the Alliance of Power and Trust between Athena and Zeus)

There is a naked man lying on a gravestone, and a woman standing on his neck, gazing out over the entrance and exit of the cemetery. She has a human heart tattooed on her upper arm.

In relationships, there is a constant negotiation and balancing act between trust and power. The image is titled Corner, because a corner is the supporting part of a building — a place of tension and strength, where forces meet and hold. Private relationships can be both life-giving and life-threatening — hence the cemetery. The action in the photograph expresses power enacted within trust, which is sometimes risky. Yet it is this tension — between vulnerability and control — that forms the foundation of intimacy.

This dynamic mirrors the mythological alliance between Nike, goddess of victory, and Zeus, god of supreme power. Their union is not just one of domination, but of mutual reinforcement: victory needs power, and power is legitimized through victory. In the same way, trust and power in human relationships are not opposites, but interdependent forces.

This dynamic echoes the myth of Athena, born fully formed from the head of Zeus — not in violence, but in a moment of divine insight. Athena, goddess of wisdom and strategy, embodies a power that is not brute force, but reasoned, relational, and just. Her alliance with Zeus is not one of submission, but of mutual reliance: she advises, he listens. Together, they represent a model of power grounded in trust.

In the background, at the top left, there is a building — a library for women’s literature in London. It stands as a quiet counterpoint: a space of knowledge, memory, and resistance.

(Analog panorama-negative, C-type print ca 229X84cm.)

(Analog panorama-negative, C-type print ca 229X84cm.)

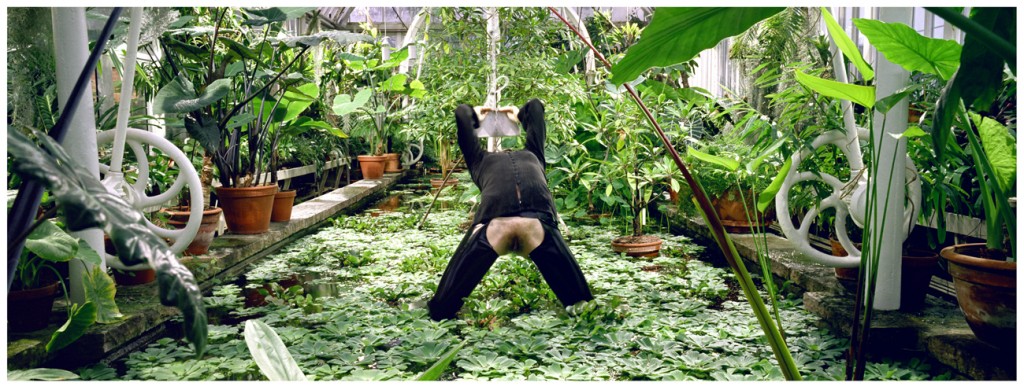

Title: ”I can see you but you can´t see me.”

”Jag kan se dig men du kan inte se mig.”

A woman — or part of a woman — is embedded in lush green vegetation. Her head is not visible, and her hands form the sign for eyes. The vagina, when exhibited, is as large as a face and looks back at the viewer, saying: “I can see you, but you can’t see me.” The title alludes to The oppositional Gaze (as theorized by Bell Hooks – scroll down and read more about The gaze). The photograph and the title play with the viewer’s gaze reversing the traditional dynamic: the vagina — gender itself — looks back. In doing so, I wanted to question and subvert how women have traditionally been seen. F.x sculptures of nude women in ponds or fountains — naked, but posed in ways that are perceived as gentle, sweet, and beautiful…normative. Here, the vagina is isolated and active; it sees. It is an active female gender. She speaks. She says: I can see you, but you can’t see me. She addresses the viewer, looks back, refusing to be passively observed or studied.

(Analog panorama-negative, C-type print ca 229X84cm.)

”Pondering how to establish communication with my cousin through global information systems — utilizing local area networks, wireless access points, terrestrial cellular towers, submarine fiber-optic cables and satellite relays.”

(Analog panorama-negative, C-type print ca 229X84cm.)

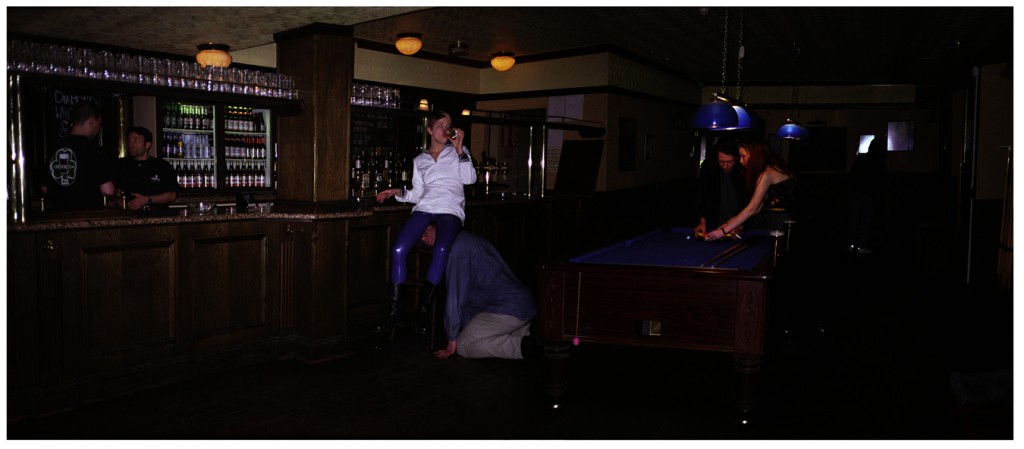

Pondering Power Dynamics at The Blue Angel Bar

This photograph was created at The Angel Bar in London as a performance for the camera. The woman is balancing, trying to find her axis and relax. The man she is sitting on is contemplating his childhood.

This act reverberates through the trembling, shifting, creative structure of society. Society is built on relationships — every private, intimate, and public act by every individual is political.

(Analog panorama-negative, C-type print ca 2,5mX1m.)

(Analog panorama-negative, C-type print ca 2,5mX1m.)

I love myself and I understand you think I´m difficult.

The photograph plays with the viewer’s gaze. It is inspired by Jacques Lacan’s theories on subjectivity and the mirror stage.

(Scroll down to read more about the concept of the gaze.)

(Analog panorama-negative, C-type print ca 229X84cm.)

(Analog panorama-negative, C-type print ca 229X84cm.)

The Fool

Pondering Socioeconomic Differences

The Fool explores an inevitable — perhaps even necessary — state of mind. To be a fool is to remain open: to the world, to contradiction, to beauty in unlikely places.

A swan lies quietly in the garbage, radiant in its own beauty. It seems foolish to build a nest in such a place — surrounded by waste and ruin — and yet: what do you realise you can do? What can you do? What do you want to do? And what do you actually do?

The image is an invitation to reflect on how we navigate the spaces we inherit, the conditions we’re born into, and the choices we make within them. Foolishness, here, is not ignorance — it is a kind of radical presence.

(C-type print 110 x 70cm) God is love

The photograph was placed at the far end of the gallery. The title appears as a tattoo on her body.

Scarring is a Secret Photo

A documentation of a scarring, accompanied by an explanatory text mounted on the wall. You hold a conception — an ideology, a belief, a position in a political discussion. But sometimes, an experience cuts through the belief behind that conception.

This is how I work.

About The Gaze

The gaze refers to how someone looks at or observes something. It is a concept used to explore how perception is shaped by the act of looking — and how power and identity are mediated and constructed through being seen.

In The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators (1992), bell hooks explores the gaze from the perspective of the spectator. I have engaged with this concept, aware of how the female body is traditionally viewed through the lens of normative expectations. By reversing the gaze, I aim to question prevailing power structures.

Theories of The Gaze have contributed to a deeper understanding of self-representation and are central to discussions about the role of vision in art and society — especially for visual artists.

Jacques Lacan, psychoanalyst and structuralist, developed the concept of The Gaze around 1956, in the context of his theories on subjectivity and the mirror stage. His ideas explore how individuals perceive and position themselves in relation to others, particularly through the psychoanalytic relationship between the subject and the Other. The gaze of the Other can act as a catalyst for desire, but also lead to a sense of objectification, where the individual internalises the gaze and forms their self-concept through it.

Michel Foucault incorporated the gaze into his theories of power and surveillance. Laura Mulvey introduced the concept of The Male Gaze, and feminist theorists such as Gayatri Spivak, Judith Butler, and bell hooks have expanded it further. Their work offers diverse perspectives on how power and identity are shaped through the dynamics of looking and being looked at.

Photographers can adopt or challenge The Gaze to evoke different emotional and intellectual responses in their viewers.

Så här svarar Kulturministern angående fotot ”Corner” i Skövde.

Fråga för skriftligt svar. Den 20 december

Fråga 2002/03:356 av Yvonne Andersson (kd) till kulturminister Marita Ulvskog om konstnärlig utsmyckning av myndigheter.

Staten byggnader, myndigheter och liknande utsmyckas med stora mängder konst. Konsten ska bidra till en god arbetsmiljö för de människor som arbetar eller vistas i byggnaderna. Konsten köps in av Statens konstråd som ansvarar för den konstnärliga utsmyckningen av samtliga statliga byggnader. Inköpen görs i samverkan med representanter från den myndighet där konsten ska placeras. Självklart är det svårt att göra alla nöjda när det gäller val av konst till en byggnad. Vissa människor kan vara mycket kritiska till en målning eller en skulptur som andra älskar. I vissa fall kan det dock finnas en bred samstämmighet kring ett verk. På Skövde högskola finns i entrén ett målning som många är kritiska till eftersom den ger associationer som inte alla uppskattar. Målningen föreställer en man som ligger på backen, och en kvinna som står på honom. Så många har nu blivit illa berörda av målningen att högskola beslutat att arbeta för att den ska tas bort. Högskolan får dock inte själva ta bort eller flytta den utan detta måste göras i samråd med Statens konstråd. Trots att högskolan tagit kontakt med Statens konstråd och förklarat att de är missnöjda med målningen har inte konstrådet gett dem tillåtelse att flytta målningen.

Vad avser ministern att göra för att öka myndigheternas möjlighet att påverka den konstnärliga utsmyckningen i deras närmiljö?

Svar på fråga 2002/03:356 om konstnärlig utsmyckning av myndigheter. Den 15 januari

Kulturminister Marita Ulvskog.

Yvonne Andersson har ställt frågan till mig vad jag avser att göra för att öka myndighetens möjlighet att påverka den konstnärliga utsmyckningen i deras närmiljö.Frågan är föranledd av en diskussion som förts efter att ett konstverk av Cecilia Parsberg, tidigare professor vid Umeå konsthögskola och en av våra internationellt mest framstående konstnärer idag, blivit placerat av Statens konstråd i entrén till Skövde högskola. Yvonne Andersson menar att många blivit illa berörda av verket och att högskolan beslutat att arbeta för att det ska tas bort, men att Konstrådet inte gett dem tillåtelse att flytta verket.

Jag delar Yvonne Anderssons uppfattning att man ska efterfråga och respektera brukarens uppfattning om de konstverk som ska placeras i den miljö som är en del av deras vardag och jag menar att det är viktigt att finna goda former för samråd så att denna uppfattning på ett lämpligt sett kanaliseras in i beslutsfattandet. Detta samråd bör präglas av öppenhet från alla parter och en ömsesidig respekt för den speciella kompetens man företräder. Men att man, även med, dessa goda förutsättningar, skulle kunna utesluta alla möjligheter till konflikter i ett sammanhang när man diskuterar och beslutar om frågor med koppling till samtidskonsten menar jag är orimligt, om det ens är önskvärt.

Som jag har kunnat inhämta från Konstrådet har de vedertagna samrådsformerna iakttagits i detta projekt. Högskolan i Skövde är ett mindre projekt utan beställda konstverk där man erbjudits möjligheten att föra samrådsdiskussionen genom att verk placerats under en prövotid. Enligt uppgift kommer det nämnda konstverket, som en följd av den diskussion som har förts mellan företrädare för högskolan och Konstrådets projektledare, inte få sin placering i Skövde högskola efter prövotiden. Enligt min uppfattning visar detta att de arbetsformer som Konstrådet praktiserar innebär att brukaren/mottagaren har ett fullgott inflytande över vilka verk som ska placeras i deras arbetsmiljö.

Samtidigt vill jag betona betydelsen av att en verksamhet som Statens Konstråds förmår att föra ut även de senaste och kanske mest krävande konstuttrycken i den offentliga miljön. Detta är en uppgift förenad med vissa uppenbara svårigheter, men som jag menar är central för verksamhetens konstnärliga och kulturpolitiska legitimitet. Dessa konstverk kräver noggranna introduktioner och andra former av uppbackning, men de kräver också ett öppet sinne från mottagarhåll inför det nya och okända.

Det är inte alltid det omedelbara intrycket av ett konstverk som blir det bestående, det är inte heller det mest lättillgängliga och begripliga verket som blir det mest betydelsefulla. Det omedelbara motstånd man kan känna inför något hos ett konstverk kan med tiden visa sig vara det som är dess viktigaste kvalitet. Att betydande samtida konstverk ändå kan visa sig olämpliga att placera i vissa miljöer hör självfallet också till denna bild. Jag har fullt förtroende för Konstrådets förmåga att på bästa sätt hantera dessa svåra avvägningar.