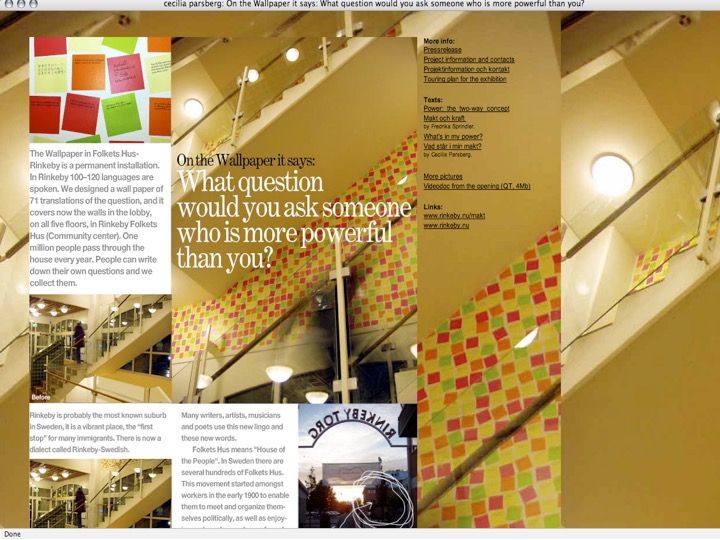

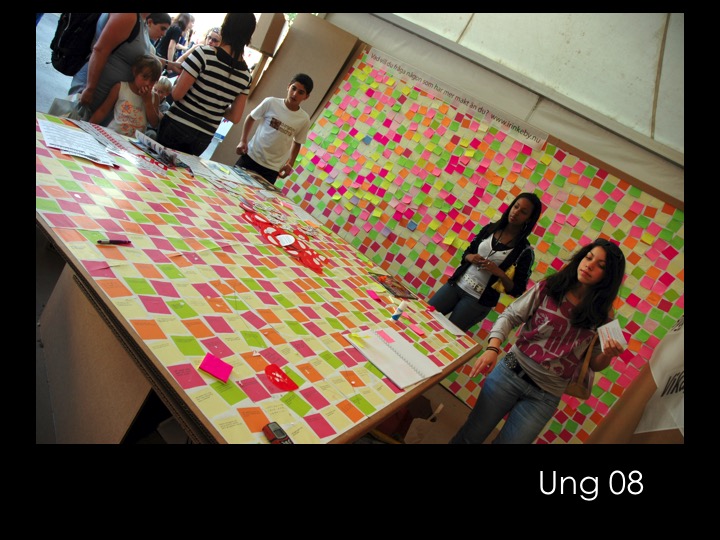

Networking on the wall

An essay by Cecilia Parsberg. Published in Glänta 1-2/2006. An English version can be found on Eurozine http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2006-05-30-parsberg-en.html (See also my reportage for KOBRA, Swedish TV, 2006)

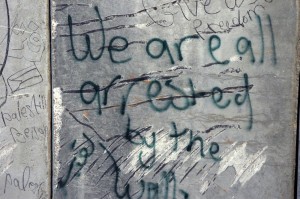

Since 2003, graffiti artists worldwide have been leaving their marks on the Palestinian side of the demarcation wall being built between Palestinian and Israeli territory.

Swedish artist Cecilia Parsberg’s photographs record what she calls ”an international multitude, a writing−carpet”. ”I am primarily interested in the phenomena of people coming from other countries to paint on the wall, and that they paint on one side of it,” she says. ”The core of this type of network is the connection between the place and activity, the clash of different aesthetic expressions, that there is no typical graffiti−aesthetic.” Are Parsberg’s photographs evidence of a larger movement of aesthetic resistance to the changing value systems of globalization in art and society? Cecilia Parsberg Networking on the wall Palestinian artists and cultural workers talk about the ”art” drawn on the wall demarcating Palestinian and Israeli territory. Their opinions are revealing of the wall’s significance in the Palestinian experience and the function of ”network as resistance”.

One hundred policemen cannot attain what beauty

is able to bring about in a violent person.

Edi Rama, Minister of Culture, Albania

In October 2005, I set off to Palestine and the wall that has become a place for collective activism and maybe also art. I bring with me Giorgio Agamben’s State of Exception, which I have been reading and reading, hoping to understand how his theories make sense in reality. I want to meet cultural workers in Palestine and listen to their views on the art on the wall. I want to know what they think about the international artists coming there and painting on it. I wonder if the multitude of works can be seen as a kind of collective creativity, a network. I am also curious why the wall is painted on the Palestinian side but hardly on the Israeli side.

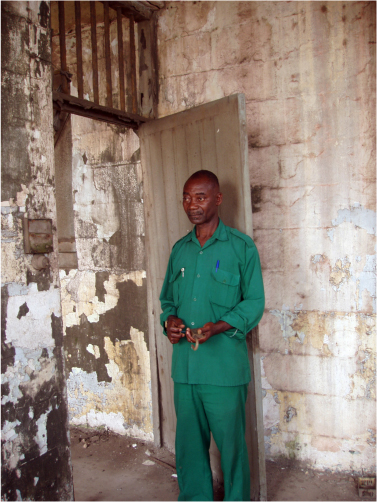

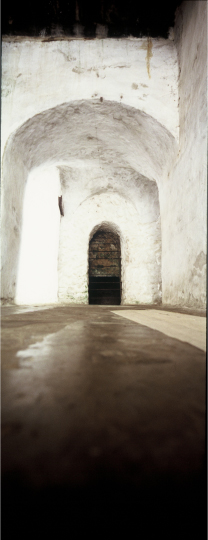

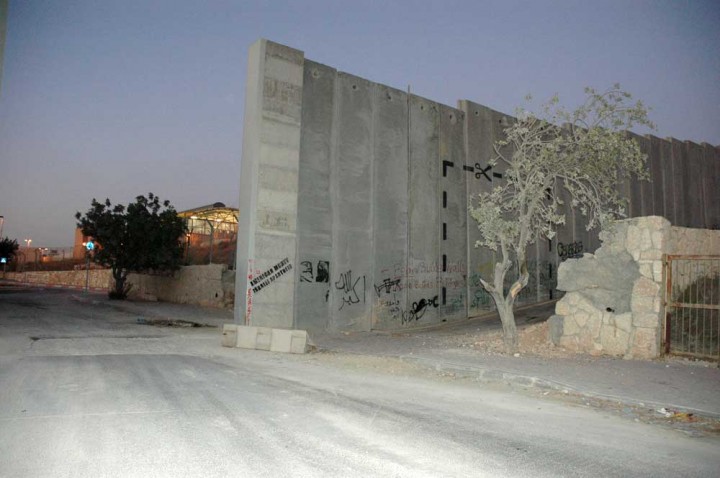

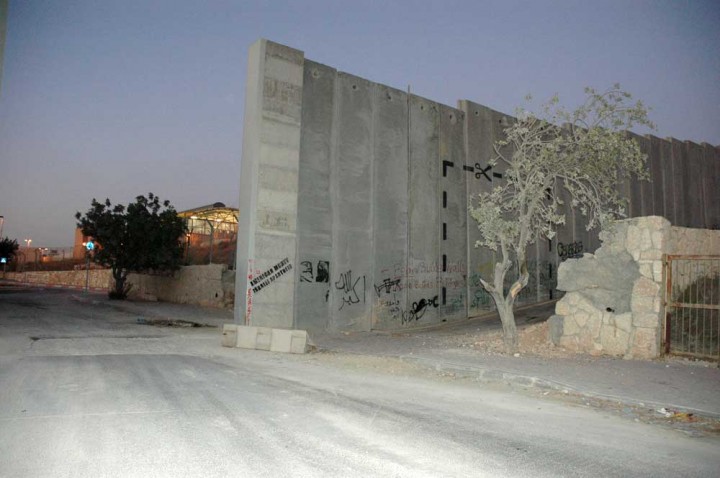

Ramalla check-point, Palestinian side, 2006

The Israeli wall is built on the Palestinian side of ”the green line”, the border between Israeli and Palestinian territory agreed on in 1967. The wall winds across Palestinian farmland, which is excavated as the wall is built. Construction started in 2003. On 9 July 2004, it was declared by the International Court of Justice to be in breach of international standards, but that has not prevented construction continuing. When the wall is completed it will be 670 km long.

The wall is not just a political barrier. It has also become a place for international and collective artworks, a surface where networking happens by itself, without the networkers knowing each other, or even the person whose image they are painting onto. The wall is a place of action and a place with great attraction for artists. Many artworks are made about it, but I am interested in the art that is made on it. The question is why artists and others from throughout the world come to paint or write on the wall. ”To show law in its non-relation to life and life in its non-relation to law means to open a space between them for human action, which once claimed for itself the name of ’politics'”, Agamben writes. Is it in this sphere that these artists are active?

Abu Dis, Palestinian side, 2006

The construction of the wall implements a state of exception, a temporary suspension of legal rights. The notion is juridical and can be activated when a country is struck by natural disasters, strikes, or civil disorder. Agamben claims that today, in practice, the entire world is in a permanent state of exception. This state is an empty space with another value system than the ordinary jurisdictional order. It is made manifest when, for example, the police stop buses and demand that passengers show their papers; when people with the wrong skin or hair colour are arrested as suspects.On 20 November I meet Galit Eliat in Jerusalem. She is the head of Digital Arts in Tel Aviv and engaged in a big project about the art on the wall, where she is curating both Israeli and Palestinian artists. She replies to my question whether there is any art on the Israeli side with the short answer that Israel wants the wall; why then, would they paint on it? For Palestinians, the wall prevents them working in Israel and visiting their relatives on the other side. (They must obtain special ID papers, and that is not easy.)

However, there are rumours about an Israeli settlement that commissioned some of their Russian inhabitants to paint landscapes on the wall. There is also a sector of a highway where stone blocks were delivered with a printed landscape. That the wall is built on Palestinian land is an additional reason why there is no Israeli activity on it. It is built closer to the Palestinian rather than Israeli residential areas, except for the densely populated areas around Bethlehem and Jerusalem. The Israelis are also creating a no man’s land on their side; they have constructed military patrol roads and a landing strip for military aircraft outside Ramallah and other military bases.

Ramallah check point, from the Israeli side, 2006

Civilian motorways are also built with high grass-covered embankments in front of the wall.

![]() Motorway on the Israeli side, 2006

Motorway on the Israeli side, 2006

On the Palestinian side, the wall separates farmland from residences, which has caused confrontations in many places. It is above all at these places that I find paintings and texts on the wall.

Graffiti by unknown people, Abu Dis, 2006

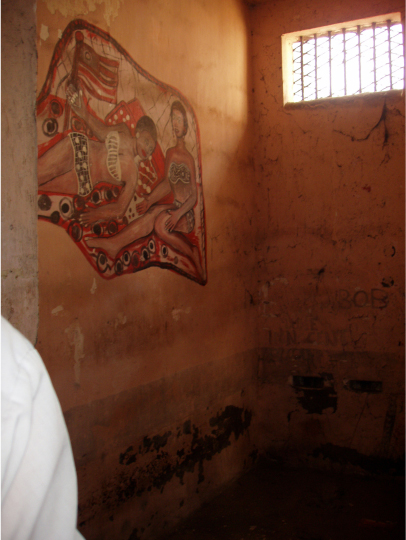

From Jerusalem I continue to Bethlehem where there are some very large murals. I photograph them. There is no one around except for a couple of armed Israeli soldiers patrolling on the other side of the checkpoint. And, of course, the surveillance cameras. How could anyone make these gigantic paintings given this surveillance? The largest is perhaps twenty metres wide and eight metres high. It is a very impressive experience to stand in front of the ugly grey wall and the paintings.

Graffiti by unknown people, Betlehem, 2006

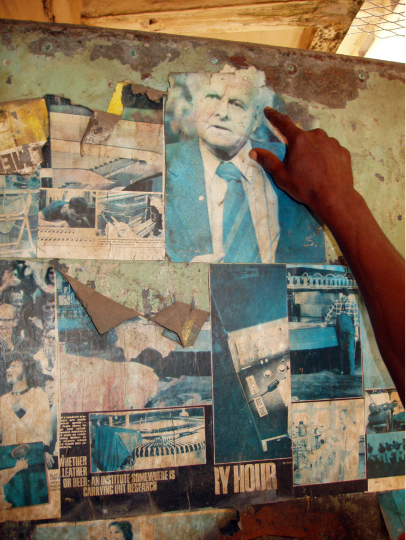

One of those who have painted is Banksy, a London-based artist who came here half a year ago and painted on the wall at around ten different places. He has not signed them, but I know them because he has become well known in the Western art world. When I ask people in Palestine and Israel, they don’t seem to know who he is. In some places, the wall looks like a gigantic scribble board, or solely like a big ugly concrete wall. The wall is ”the ultimate tourist site for a graffiti artist”, as Banksy put it.

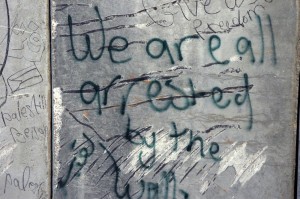

In Ramallah and nearby villages, I find two-hundred-metre stretches of wall with paintings and writings. It is an international multitude, a writing-carpet. I can’t call it scribbles, but is it art? Art is a way to represent and communicate, a way to make contact with oneself. But the paintings on the wall are also creative attempts to transcend the political limitations of the wall.

Graffiti by Banksy, Abu Dis, 2006

Graffiti by unknown people, Abu Dis, 2006

I am surprised that after a few days at the wall, I feel happy, strong, and maybe even hopeful. I can only explain this as the influence of the art on the wall. The effect reminds me of love messages, like ”I love you” cut into a tree. But these activists and artists have not been concerned to leave their names; it’s not authorship that’s important. There are no tags, either – images and texts melt together. Is all this an attempt to create art or meaning collectively?

Ramallah, the morning of 22 November 2005. I am on my way to a meeting with Faten Farhat, head of the Sakakini Cultural Centre. I pass Ramallah City. The shops are not open; they are usually open at this time, but today is a day of national mourning. I meet a tired Faten. She says she has been up all night because one of their employees has been killed in the bomb attack in Amman, Jordan. The day before, they had been planning which flowers he would have had at his wedding. He was thirty-six.We start to talk about the wall. As head of the Sakaini Cultural Centre and active curator for artists on an international art arena, she receives piles of suggestions from art institutions and artists for art projects on the wall. Most she rejects. One of the most spectacular suggestions came from a clothes designer in New York, who wanted to put on a fashion show at the wall, together with top models. She smiles sadly and says that many don’t even try to imagine how the wall affects the Palestinians. Would Palestinians go to the wall that prevents them going to work, the wall that separates families, to watch a fashion show with the latest fashion from New York? She is not against the fact that art is made on the wall, but she thinks that the projects have to derive from an ethical perspective. She thinks there is a risk that the wall becomes institutionalized, that it will be accepted as something that will stay forever. But she also says that she often leaves the project propositions further to artists in Ramallah, that she doesn’t have time to be fully updated on how they develop. She has, herself, only seen the wall twice – there are many who choose not to see it at all. Her hand moves from her belly to her throat: ”It exists within us”.

Cecilia Parsberg: There are a lot of paintings on the wall. Israelis have also left messages on the wall. What do you think about collaborative works between Israeli and Palestinian artists?

Fatin Farahat: As an institution, we don’t work with Israelis, not because there are no good Israelis, but simply because we need to be consistent. For example, an artist wanted to show Palestinian and Israeli artworks in Paris. He came to me wanting help. I said: the board and I have decided that, until a more just solution exists, there is no need to work with Israeli artists. This is not to say that we don’t encourage our artists to work with Israelis, or that we don’t allow them to. It’s up to them. I tell them that the first thing they need to do is to have a statement, a political statement from the Israeli artists, because as far as I am concerned, one of the artists could be from Likud [the Israeli rightwing party], so try to work on a joint statement that actually says that occupation is wrong, that there is something called the right of returnees, that the wall is wrong, and that that is the basis upon which we want to work together. So in every joint project, and this is the most difficult part, to get the partners to say, prior to working, that they have a very similar, if not the same, political vision of the situation. Otherwise, if you start working with different political visions, the human contact is going to be almost impossible, and the concept of the project will be destroyed. It’s much more difficult for art institutions to make joint works because it’s very difficult to reach these kind of agreements. Sometimes it’s easier on an individual level. There is another thing: if, say, an Israeli institution receives government subsidies, we have a problem. Not with the people, but with the government. If the subsidies come from the Israeli Ministry of Culture, which marginalizes Palestinians culturally, I really don’t want to work with them.

CP: Are Palestinian artists in general aware of this? And would you say that international artists in general are aware that art plays an important political role?

FF: It depends on the artists. For example, I see awareness among those who come and live with Palestinians for a while. Art is a dynamic process in the public sense, too. I am totally in favour of public art, not in the sense of putting up a public monument in the town, but by having the community participate in the creation of the artwork. International artists – I see it all the time – come to me with an idea that looks beautiful on paper, but the moment they see reality they rethink the project, because reality dictates facts. If the focus is the community as such, you need to know it, and to really know the people takes time and patience.

I know the power of the media, and I would like to see models that show real investigation and real commitment to the political issues that are actually ruling the area. International artists need to spend the time you are spending to know the people, to get a feeling for the place. I know from many of my international friends working in Palestine, after two months they have to get out, the siege is getting to them even though they have more freedom of mobility than us.

The next day, at the Art Cafe in Ramallah, I meet Akram Safadi, a Palestinian artist and photographer.

CP: What do you think about the art on the wall?

Akram Safadi: On one side, I think it’s useless, and on another side, I appreciate the political context behind it. I appreciate people coming here in solidarity with us. It’s a popular form of civil resistance against the wall. People still insist on practicing this form of resistance, it’s part of a mass action.It’s adding something human, warm, to the inhuman background the wall constitutes. The designs and paintings transform the surroundings, but the wall itself exists as such and must not become part of a normality. It’s something strange that should be resisted.

Graffiti by unknown people, Abu Dis, 2006

CP: How do you see the role of Fine Arts in an international perspective?

AS: Art grows but it doesn’t change anything. It’s more important that the control of distribution of art and the production of art be seen by the public. Media is too much in control of what is seen by people; it doesn’t promote plurality. My opinions are always manufactured by the information that is selected and delivered by the media. That puts a big question mark behind the concept of democracy.

That evening, I have an appointment with the poet Kifah Fanni and the artist and animator Amer Shomali at Stones, an exclusive bar situated in downtown Ramallah.

CP: What do you think about beauty? Do you think the paintings make the wall beautiful?

Amer Shomali: I want the wall to be destroyed, and as an artist I think that when one does something on the wall, it should be like a protest against it, not a piece of art. The important thing is the message. If you build a relation between the wall and your artwork, then you want neither to be destroyed.

Kifah Fanni: I don’t believe the painting is institutionalizing the wall; I don’t see it as acceptance of the wall. Especially the painting where the wall is removed like a curtain showing a view behind, or the one that draws a window on the wall, or Amer’s animated film, where a boy draws a wall on the wall and a dove flies through. It’s a virtual view; the Israelis can limit our sight, but they can’t limit our imagination.

Graffiti by Banksy, Abu Dis, 2006

CP: Do you think the art will have a political impact? I can’t help thinking that if paintings were also made on the Israeli side, it would influence the discussion there.

KF: No, it would be totally different. On the other side, they see the wall as constructive. There could be good paintings made on the other side, but only as absolute negatives, you know, the opposite message.

CP: But the paintings you mention were made by a London-based artist. He might as well have made them on the Israeli side.

KF: Then it would have been other paintings. You can’t paint the same on the other side.

CP: Why not?

KF: Because it’s their will to build this wall; it’s against our will. From our side it’s inappropriate: we want to demolish this wall. If an artist wants to express an Israeli will or aspiration on their side of the wall, he or she would draw another wall on the wall. These people think we are explosive, that we have this explosiveness.

CP: Do you know if there are any Palestinian artists who want to go to the Israeli side and paint something?

KF: You would have to ask if there is any Palestinian who is allowed to go to the Israeli side… I am not underestimating the importance of art, but on a certain level, it’s not a matter of taste. If you are hungry, you eat anything – taste will not be the criteria. And this is how it is; first you move, then you decide if you want to go or not.

CP: But the criteria, and I have to insist on this point, for someone who lives in London, Sweden, Germany, or Italy, and comes here to paint, is different. He or she can choose which side of the wall to paint on.

KF: Are they allowed to?

CP: No, but when did that stop an artist? Graffiti art has been illegal since it was born.

KF: Yes, but you talk about graffiti art in a civil context. Being caught here is not the same as being caught writing graffiti in London. You are convicted for that, you can die for that – for writing words on a wall. It’s not like expressing socialist or capitalist views. It’s about living or not living, the contradiction here is too strong. When a Palestinian goes to write graffiti, they wear a mask, with someone on guard. It’s a big deal. We used to do it when we had poor access to media. In the old days we had typewriters, and each typewriter on the West Bank had a serial number. The Israeli government had these numbers, so it was extremely dangerous. If you had to print pamphlets, it was made with the same degree of danger.

CP: Still, if you are a person from another country and you think ”fuck this wall, I don’t like it, I want to destroy it”, you can choose where to paint your message. That would be to direct a protest that would face the Israelis.

AS: We don’t have that choice. Try yourself and tell me what you have drawn.

KF: There’s a significance that precedes the drawings on the Palestinian side. For the majority of the people on the Palestinian side, it’s allowed, even if it’s not always appreciated. But on the other side, you have a hostile environment.

AS: The Israelis don’t have contact with the wall as we have, because the wall is mostly far from their houses.

CP: Why is it far away from the people?

AS: Because they want more land without people on their side. Most of the Israelis don’t know what the wall looks like, only those people living in distant settlements, like near Jenin. In the Israeli cities they have only heard about the wall in the media. Here in Ramallah we have daily contact with the wall, we are touching it. The people in Tel Aviv won’t go to Bethlehem to paint on the wall. On the other side of the wall there is nothing built, because it was recently, before the wall, our land. Now they are constructing roads. If you drew something on the wall on the Israeli side, there wouldn’t be anyone to see it. What’s the point then?

CP: Just outside the wall at the Kalandia checkpoint [the checkpoint between Ramallah and Jerusalem] the Israelis have built a runway for military aircraft. It’s a security area guarded by stray dogs, really dangerous even to photograph.

AS: It’s useless to draw on the other side. You can reach the Israelis better through media.

KF: It becomes my physical border, my own limitation. Before it’s national, it’s an assault on my individual view.

Graffiti, Betlehem, 2006

AS: It’s not an ethical problem. Maybe it is for foreigners, but for me, it’s an existential problem.

CP: But an art project doesn’t have to be ethical?

KF: Those on the Israeli side willing to make a statement can make joint projects with us. Foreigners come here with their free imaginations, they don’t know the limitations, they want to start a revolution, they don’t know what’s really going on. We spent too much time being lectured to on how to make a revolution, but those lectures don’t bear in mind the forty years of occupation. The idea of revolution is out of context. But sometimes we have to learn from the young, because this long conflict has been a bad experience for us. When a child sees a snake, they want to touch it; when an adult sees a snake, they run away. The Palestinians who praise the intifada are the innocent ones. They are like the foreigners who come here and cannot believe their eyes. That’s why they have extremist ideas and concepts. This is what’s happening to the Palestinian youth, who are checked on each checkpoint. This is not acceptable, we are all born innocent and naive. This is why the intifada took place seven to ten years after the first: when a generation reaches, let’s say, the age of wisdom.

AP: I made a book and animation collecting thousands of drawings from Palestinian schoolchildren. The way that children express themselves on the issue of the wall is very innocent, pure, irrational. It’s not logical to destroy the wall with your naked hands, or with your eyes, or to open a box and find Jerusalem. I imagine myself trying to deal with the wall, looking for the simple ways.

Graffiti by children in Ramallah, 2006

KF: Artists have to go back to childhood, childhood is the master of art. Before we regain innocence, we cannot produce art.

AP: Foreigners are innocent due to a different setting, they don’t live our conflict, our setting. We are born into a place where there are checkpoints, we can’t imagine a life without checkpoints. For international visitors it’s possible to imagine a life without occupation.

KF: People should dare to dream. International art projects and ideas should dream about destroying the wall. I have not examined further if collaborative works have been made between Palestinians and Israelis, or what their agreement looks like. Networks don’t necessarily have to cross borders. I am primarily interested in the phenomena of people coming from other countries to paint on the wall, and that they paint on one side of it. The core of this type of network is the connection between the place and the activity, the clash of different aesthetic expressions, that there is no typical graffiti-aesthetic.

Eugenio Molini works with Managing Diversity, a network of consultants specialised in issues of diversity. Back in Sweden, I ask him how he defines a network. He answers that networks are based on passion, that the networkers act through ”swarming”. The driving force can be personal or collective; the organizational principle is founded on engagement and responsibility, responsibility for one’s own actions. While participants in a group or a constellation are ”in” or ”out”, the individuals in a network are connected or disconnected, which in principle means that the network develops into something else. Molini argues that the need for resistance doesn’t have to be the reason a network is created – an example of the contrary is the pilgrimage.

Graffiti by Palestinian artist, Ramallah, 2006

Inside and outside Palestine, a Palestinian artist is first a representative of Palestine. There are few actions strong enough to go beyond that role. But if this is the case, what do the anonymous artists who paint on the wall represent? Are they participants in a bigger movement reacting to the changing value systems of globalization within art and society? The nine-metre-high Israeli wall separating people from people seems to function as blotting paper for artists and activists, at the same time as being a manifestation of a hidden agenda that doesn’t care about international law. Many of the paintings show openings in the wall: doors, windows, sky; they ”dissolve the wall” and could, in a way, be read as metaphors for communication, for the Internet and the digital boxes that transmit all the channels in the world. (Digital television is more common in Palestinian homes than in Swedish). It is not the aesthetic expression that is the mutual denominator, it is the message.

Graffiti by Banksy, Betlehem, 2006

The Israeli wall is not the only wall being built worldwide. Are walls being built primarily to separate poor and rich? The illusion of freedom is a necessity for every person, but freedom for a poor non-European may be to get inside the European wall, while freedom for a rich European is to keep that person away. On their album The Wall (1979), Pink Floyd portrayed a school system where corporal punishment was still normal. The wall they sang about was a mental wall, a border behind which society exercised sanctioned violence, all according to the rules of the school. But if the difference between the system of rules and life is too big, a kind of violence is exercised on what the citizen understands as justice. Life is, according to Pink Floyd, a product of the machine. ”Welcome my son, welcome to the machine. Where have you been? It’s all right, we know where you’ve been. You’ve been in the pipeline […] And you didn’t like school and you know you are nobody’s fool.”

Around the Israeli wall, two opposite forces act, one that institutes and makes, and one that deactivates and deposes. ”Bare life”, writes Giorgio Agamben, ”is a product of the machine and not something that pre-exists it, just as law has no court in nature or in the divine mind. Life and law, anomie and nomos, auctoritas and potestas, result from the fracture of something to which we have no other access than through the fiction of their articulation and the patient work that, by unmasking this fiction, separates what it had claimed to unite.”

Pink Floyd sings about an invisible wall, a wall is taking shape on the record. The Israeli wall is concrete, which doesn’t hinder the art and fiction partly dissolving it. In both cases, art is a political action, an action that severs the nexus between violence and law, and instead opens a space for negotiation between life and right.

Graffiti by Banksy, Betlehem, 2006

an essay by Cecilia Parsberg, also published at:

http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2006-05-30-parsberg-en.html

Reference:

State of exception, Giorgio Agamben, The University of Chicago Press (2005)

http://banksy.co.uk/

Cecilia Parsberg reportage for KOBRA, Swedish TV, (2006) on the paintings on the wall with focus on BANKSYS graffiti.