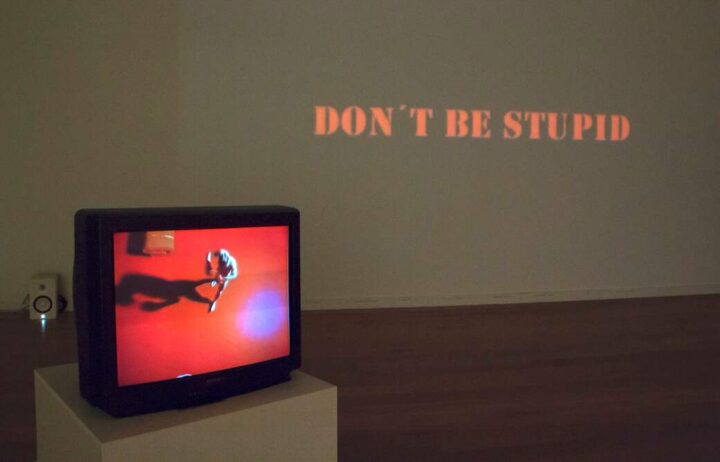

Don’t be stupid (1997) consists of two films: a main film (3:56 mins. screened big) of the boxing woman and the man, plus a companion film (20 sec. screened small) with only the man.

”Cecilia Parsberg’s blood-red boxing match, in which a naked woman in a furious rage attacks an equally naked man who tries fruitlessly to protect himself behind a rolled-up mattress, is as hilarious as a Laurel and Hardy film. But at the same time it evokes chilling associations with the Metoo movement and everything that happened in connection with it.” writes Sara Arvidsson, GöteborgsPosten 1/4,2021 about the installation, in the group exhibition ”Generation” at Borås Konstmuseum 2020-21.

”The woman’s blows to the man can be juxtaposed to a structural fight against the prevailing view on gender. The outcome of the boxing match, with the woman exhaustedly collapsing, can be seen as inevitable as the struggle against the patriarchal gaze is destined to be lost. The work is addressing structural powerlessness in political relationships, shedding light on contemporary Swedish society.” writes Sofia Ringstedt, Magasin III.

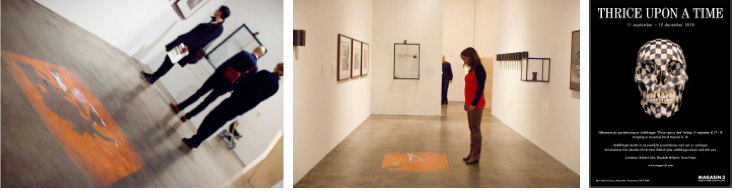

Screenings: Stockholm Art Fair. SVT “Elbyl” Ch 1 / Art & Video in Europé Heure Exquise! Stockholm Art Fair. Swedish Television Ch1 / Osnabruck Videofestival. at Botkyrka Konsthall. Don ́t be stupid in the videocompilation ”Take two” (same tour as FRESH) at: the ICA, London / Videopositive-95, Liverpool / Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff / Ikon Gallery Birmingham / Tate Gallery London / Ferens Art Gallery Hull / Open Hand Studios Reading / National Film Theatre in London / Ruskin SFA Oxford. ”The king is not the queen” (1998) curated by: Francesco Bonami at Nordiska Museet one exhibition of ”Archipelago” Stockholm Capital of Culture, Magasin 3, Stockholms Konsthall, Borås Konstmuseum, SSE Art Initiative, Stockholm. Don’t be stupid, as projection on the floor Sept-Nov 2011, Magasin 3, Stockholms Konsthall.

Don’t be stupid, as projection on the floor Sept-Nov 2011, Magasin 3, Stockholms Konsthall.

The man in the performance says: Woman kicks man’s ass. To me it would seem more natural with the roles turned around, a man punching a woman. Then I would sympathize with the woman.

The man in the performance says: Woman kicks man’s ass. To me it would seem more natural with the roles turned around, a man punching a woman. Then I would sympathize with the woman.

I would probably see the video as an image of women’s relation to men in general. I can easily sympathize with the woman when she’s the one wearing the boxing gloves. With the woman fighting it’s so obvious to me, as a man, how lonesome her struggle is. She doesn’t let the man in. This is not the picture of a relationship, rather it reflects the fight of a single individual.

I’ve always believed that the relationship between man and woman in our society was the concern of both. Why does it seem so clear to me in this case, that it’s all about one individual woman struggling with herself. Is this the kind of one-sided struggle that patriarchy is built to hold and maintain?

The woman spends all her energy on her fight. What happens to the man – nothing?There is no room left for him. And in our society-where is the deliverance of women made passive by someone else’s fight. Men struggling, leaving no room for women. What happens to women-nothing? Should you implode or explode?

It’s a man’s world, in which both men and women live. But society is no relationship – it’s a one-sided struggle for survival and self-development – man against nature – men against women!

Cecilia on the film installation:

This film could be read as ”A no is a no”! as proposed by the critic (at the top). But art is, and should be open for every viewers own interpretation, depending on personal and political experiences, memories and associations. In this way, art is democratic, it opens up a forum.

However, I would like to say something about working with images. This film was made in the postmodernist 1990s when the discussion about the importance of the image was intense. In the 1970s, theorists such as John Berger and Erving Goffman had written about the voyeuristic gaze and how the body language of men and women was often mediated by stereotypes of the ”passive woman” as an object to be examined, scrutinised and judged in contrast to the ”active man” (Liz Wells 2023, Photography a critical introduction, ed.6. p.297). When I started working with video art and photography in the 90’s these notions were still prevalent, I knew that working as an image maker would involve judgement and selection of what is worth capturing and that it is a responsibility. As a woman, then 34 years old, I often felt trapped in the eyes of others and that I needed to break away from the ’given images’ that I felt were glued to me. I sometimes had an abstract feeling that I became flat, two-dimensional in front of the voyeuristic gaze, like a postcard (today’s social media) as if I was described by the term ”representative woman”. I felt that the mental and physical images that existed in society, of how I was expected to be, behave and live, were hindering me and I wanted to make myself three-dimensional. I wanted to activate the prevailing (mental and physical) images and at the same time the viewer’s gaze. I articulated myself mainly in images; painting, photography and film, I didn’t write much. So the raging woman also struggles against prevailing images of how she should behave, and at the same time how the man should behave, and struggles to break free from limiting, culturally agreed stereotypes that circulate in society.